Over the years, several theories of design have been proposed by researchers. The study of engineering Design is integral to the study of Manufacturing System Design for two basic reasons:

Let us first look at what happens in any typical manufacturing system, in terms of broad activities:

Figure 1. The Activities of a Manufacturing System

I am using the following definitions:

Product Realisation Process: All activities starting from the first conception of a new product till the product begins regular production in the factory. The activities include initial design, detailed design, building design prototypes, debugging, design of tooling, pilot runs, customer feedback, burn-in tests etc.

Process Plan: Activities include generation of detailed process plans based on the designed tooling and the facilities available, make-or-buy decisions, etc.

Production: Actual production based on orders, including decisions about job sequencing and scheduling, quality control etc.

Notice that the design of the manufacturing system emerges from the product realisation proces.

It is therefore important for us to study in some detail methods of design.

Classes of Engineering Design Methods

Theory Based

Suh (Axiomatic Design)

Taguchi methods

Altshuller (TIPS)

Empirical Methods

Pahl & Beitz (Systematic Design Approach)

Boothroyd (Design for Manufacturing and Assembly, DFMA)

WDK (Workshop Design-Konstruction; procs of ICED)

Vision Based

Quality Function Deployment (QFD)

Product Design and Development (Ulrich and Eppinger)

PRODEVENT

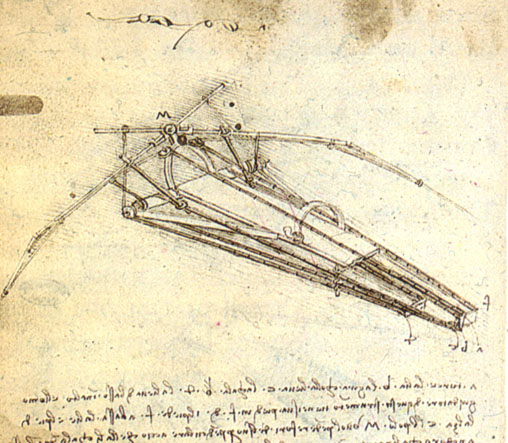

The questions, in sequence, relate to inventive product design (e.g. see figure 2), design of manufacturing systems, and operation of the manufacturing systems.

Figure 2. Leonardo Da Vinci's Ornithaptor (bird machine), conceived around 1488 AD. Lying on the board, the human was to operate the wings using a system of pulleys with his arms and legs. Source: http://banzai.msi.umn.edu/leonardo

In the following, I will introduce the fundamentals of three design methods. We first look at Inventive Problem Solving (TIPS) methods of Altshuller. Next we study Axiomatic Design (Suh), and finally, we see how the axiomatic design method is related to the powerful and popular Taguchi methods.

The basic philosophy behind TIPS can be summarized in the following:

The theory is developed into a methodology (procedural), and even marketed as an interactive software called the Invention Machine. Its differences from traditional engineering design teaching are highlighted by the following example:

A supporting pile needs to be driven into soft ground, deep enough to provide support for some construction above the ground. Three cases are shown in the figure. If the pile is blunt, it needs a large driving force to put it into the ground, but it is subsequently very stable in use. A very sharp pile is easy to drive into the ground (low force, P2), but any construction built on such a pile will sink into the ground easily, and is therefore unstable.

Traditional engineering wisdom in such a case is to model the driving force and the pile stability as a function of the pile angle, and to optimize the pile cone angle.

TIPS suggests that this is an example of tunnel vision. We are limiting our design to the pile solution in hand, and only changing the pile geometry parameters that have been linked to the geometry.

It could be better to look at the problem in more fundamental way: The objective is to obtain a pile in the ground that is: (a) easy to drive in, and (b) stable under large weights. One suggestion which can result in both these objectives is shown in the following figure.

Here, the sharp point of the hollow pile is used to drive it deep into the ground, and the explosive is then used to generate a blunt cavity, which is unified with the pile by pouring in concrete.

The first fundamental insight from TIPS is therefore the following:

Contradiction is an opportunity for invention. This is in contrast with

traditional engineering design, where conflicting objectives lead to to

attempts to trade off, by using optimisation/compromise/negotiation.

Another basic idea behind TIPS is that the inventor must, by a series of questions, arrive at the very essential functions that must be satisfied, and specify simple constraints between them. They then claim that once you pin point the very essential functions, there must be either some existing/known physical phenomenon that can yield this function, or some know previous invention that does the same task.

They further claim that any inventor cannot, at any given time, know, or even recall all such phenomena. TIPS therefore consists of two components:

Over 2500 known engineering and scientific effects, including Physics, Chemical and geometric effects

An interface in which the user can type the problem;

An interactive mechanism to convert the statements into simple sub-tasks and constraints between the sub-tasks; and

Methods which can match each phenomena with existing database entries that can perform the sub-tasks.

The software (Invention Machine, or IM) helps in two ways: (a) it forces the designer to break down the task requirements into the very essential ones, and (b) it gives several alternative solutions, some of which may be useful.

It is required to design an electrical switch which can conduct large currents, but needs to be of small volume.

The common design of such switches uses two flat conducting plates which can be brought into contact (CLOSED position) or taken apart (OPEN position).

For the small volume requirement, we can reduce the size of the plates -- but this leads to higher resistance at the interface and therefore not good.

The TIPS system will question the designer till it discovers that in fact the contact resistance is inversely proportional to surface area (not volume), and thereafter suggest solutions for the contacts which can have small volume but large surface area. The figure below shows some suggestions.

One of the results of the TIPS process is Trimming. Trimming is the elimination of those components of the design that are inessential for any functional requirement.

A component that performs a task on an object can be trimmed if:

In a design, it is advisable to trim parts that are expensive, or create problems, or are far from the main function.

Trimming Example:

Designers of the Soviet space probe to the moon, LUNA-16, needed to install lamps on the probe. The lamps, due to the high inertial forces during take off, would break at the point where the glass bulb was connected to the body.

A designer of the space probe, Dr. Babakin, wrote that this was a severe problem.

In fact, the problem was non-existent: Since the moon has no atmosphere, there was no need for the lamp to have a glass bulb at all (which is needed on earth to create a vacuum/inert atmosphere around the filament so that it does not oxidize when lit up.)

In summary, here are the trimming rules: Suppose A acts on B. Then:

Here is a link to a short document summarising the essential ideas in TIPS.

While TIPS is mainly focussed on product design, the methodology can equally well be applied to Manufacturing Systems Design.

In particular, the methodology of asking questions to reveal fundamental requirements, their inter-relating constraints, and trimming all inessential systems can lead to more robust as well as efficient Manufacturing Systems.

In the next section, we shall study Suh's Design Axioms, and their connection with Taguchi methods. Here are some basic references for Axiomatic design:

I have also placed a copy of notes on Taguchi Methods, written by Prof Kwok Tsui in the course handout.

These notes are closely based on the lecture material of Prof Gunnar Sohlenius, used during IEEM 513 Mfg Sys Design, Spring 1998 at HKUST.